Biophilic Cities are cities that are returning to the origins of nature. Thanks to Eric Sanderson of the Wildlife Conservation Society at the Bronx Zoo, we can explore the native Lanape place, Manhatta, meaning the *island of many hills, as it looked in the past in the 1600s, and how it might look in the future, 400 years ahead. Today, many architecture students call cities they are from *urban concrete jungles. Such cities overlook nature and strip the very lands of the nature that were present, destroying the topsoil, removing forests, draining wetlands, and eradicating flora and fauna from the grasslands.A biophilic city is a city that intentionally weaves nature into everyday life, so people experience trees, shade, water, daylight, and living ecosystems as part of their daily routines. In biophilic cities, nature is treated as a core urban system, as it connects parks, greenways, forests, wetlands, and grasslands, all filled with indigenous plants and biodiversity. Biophilic cities support Nature’s presence, improve public health, reduce heat, manage stormwater, and strengthen community life. Biophilic cities restore Nature’s ways, making cities more livable and restorative while making them more resilient to climate change. How can your city become more biophilic?

Activity 1 – What makes a city Biophilic?

A biophilic city is one that intentionally weaves nature into everyday life, so people experience trees, shade, water, daylight, and living ecosystems as part of their daily routines. In biophilic cities, nature is treated as a core urban system that connects parks, greenways, forests, wetlands, and grasslands, filled with indigenous plants and biodiversity. Biophilic cities restore Nature’s ways, making cities more livable and restorative while making them more resilient to climate change. Biophilic cities are built around performance, not aesthetics alone. Biophilic cities support Nature’s presence, improve public health, reduce heat, manage stormwater, and strengthen community life. Trees cool streets, green stormwater systems absorb runoff, and connected habitats support biodiversity. When these elements spread through ordinary streets and neighborhoods, nature stops being “a destination” and becomes part of daily urban life.

Where in your neighborhood do you experience nature without planning for it?

Activity 2 – Health, Focus, and Well Being

Biophilic design works because humans respond strongly to nature, even in small doses. Walking under a canopy of trees, sitting near plantings, or seeing water and sky can reduce stress and mental fatigue. Over time, these repeated moments help make cities feel less exhausting and more supportive. Biophilic cities tend to strengthen public life because comfortable green spaces invite people outdoors, encourage walking, and create settings where neighbors interact naturally.

This matters most in dense districts, where residents may spend long hours indoors or surrounded by traffic, screens, and noise. A biophilic approach creates “restorative pauses” inside the city’s everyday rhythm; moments that help people recover attention and mood without leaving the urban environment.

What kind of nature restores you fastest: shade and trees, water, open sky, or wildlife?

Activity 3 – CLimate Resilience

Biophilic cities treat nature as working infrastructure. Tree shade and evapotranspiration reduce heat at street level, improve comfort, and lower air-conditioning demand. When rain falls, landscapes such as rain gardens, bioswales, and green roofs, slow runoff and absorb water, reducing the risk of street flooding and decreasing pressure on sewer systems. Over time, these systems can also improve water quality by filtering pollutants before they reach rivers and lakes.

The real advantage is that this infrastructure is visible and shared. People can see where water goes after a storm, and they feel the difference between a shaded street and an exposed one. Biophilic design builds resilience while also improving everyday experiences.

If your city invested in one strategy first, would shade trees or stormwater landscapes make a bigger difference?

Activity 4 – Biophilic Design

Biophilic design succeeds when it operates at multiple scales. IN a city it means a continuous canopy where possible, shaded sidewalks, planted intersections, planted balconies, and other “nature moments” along daily routes.

At the building level, it means daylight, views to greenery, courtyards, terraces, and roof spaces that invite people outdoors. At the neighborhood level, it means connected parks and greenways, with nature as a network rather than isolated islands.

What matters most is continuity. A single park is valuable, but a connected sequence of green streets, courtyards, and corridors can reshape daily life. When nature becomes part of how you move through the city, it stops being occasional and becomes habitual.

In your area, would one large park or many smaller connected green spaces change daily life more?

Activity 5 – Biodiversity

A Biophilic City supports all forms of life. That means planting that feeds pollinators year-round, using native or habitat-supporting indigenous species when appropriate, and designing layered landscapes that provide shelter and ecological structures. It also means connecting habitats so wildlife can move through the city rather than being trapped in isolated patches.

Biodiversity also depends on maintenance. Healthy soil, thoughtful irrigation, and reduced chemical use matter. When biodiversity is taken seriously, the city begins to function like an ecosystem in pieces; still urban, still human-centered, but more alive and resilient than standard landscaping.

Where in your city could one continuous habitat corridor realistically be created? Could it be a ‘Rails to Trails’?

Activity 6 – Biophilic Implementation

Biophilic goals become real through governance and long-term care. Cities that succeed set clear targets, embed nature requirements into policies and street standards, and fund maintenance as a permanent responsibility rather than a one-time cost. They also measure progress so the city can learn and adjust over time; tracking canopy coverage, park access, heat hotspots, stormwater performance, and biodiversity health.

Equity is essential here. If nature investment happens mainly in wealthy neighborhoods, the benefits of cooling, comfort, and health become uneven. Some greening projects also increase property values, so biophilic planning must be paired with strategies that protect residents and keep neighborhoods stable. The best biophilic cities do both: they expand nature and strengthen fairness.

What is the most meaningful metric for a biophilic city: canopy percentage, “10-minute access” to parks, heat reduction, or biodiversity?

Activity 7 – Real World Examples

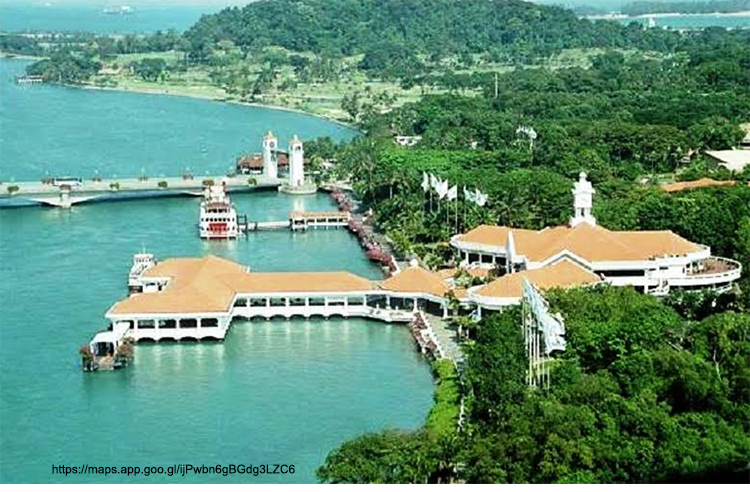

Singapore’s biophilic strength is not just “lots of greenery”; it’s the way nature is organized as a connected system people can use daily. The clearest example is the Park Connector Network (PCN): an island-wide network of green corridors linking major parks and nature areas, with more than 380 km of trails. That’s biophilia at the mobility scale; nature isn’t only a destination, it becomes part of commuting, cycling, and everyday movement. A second powerful example is how Singapore turns “hard infrastructure” into a public landscape. At Bishan–Ang Mo Kio Park, a 2.7 km straight concrete canal was transformed into a sinuous, naturalized river that meanders through a 62-hectare park. Instead of fencing water away, the design uses the park as a floodplain: on calm days, it supports recreation along planted banks, and on storm days, it temporarily stores water. The project is also known for improving capacity; one report notes the new river system can carry about 40% more water than the previous channel. If your city could do only one “Singapore move” in the next 5 years, would you choose a connected green trail network, or one major canal-to-river public-space transformation?

Activity 8 – Real World Example: Portland, Oregon

Portland sets a strong example because it makes biophilia feel like a repeatable street detail, not a special mega-project. Green Streets in Portland are essentially planted stormwater systems (often rain gardens/bioswales) integrated into streetscapes to slow and absorb runoff, reduce sewer backups, and keep pollution out of rivers. The story becomes tangible when you look at the timeline and scale. Research documenting Portland’s program notes that one early milestone was the NE Siskiyou green street facilities (2003); small pilot projects that helped refine design details before scaling up. From there, Portland scaled hard. A City of Portland ordinance document (on maintenance contracting) states that the Bureau of Environmental Services maintains more than 2,500 green street stormwater facilities across the city, meaning this is not “a few showcase rain gardens”; it’s a citywide landscape system embedded in the right-of-way. Portland also solved a less glamorous but crucial problem: who helps take care of all this landscape? It runs a volunteer program that allows residents and businesses to adopt planters and help with fundamental upkeep between City maintenance visits.

Would you rather build a few large stormwater landscapes in parks, or many small Green Streets across neighborhoods—and why?

Activity 9 – Melbourne, Australia

Melbourne’s example is powerful because it turns biophilia into measurable commitments and long-term management. Its Urban Forest Strategy sets a clear canopy target: increase public realm canopy cover from 22% to 40% by 2040.

But the truly “copyable” part is that Melbourne doesn’t only plant more trees; it designs for resilience through diversity. The strategy sets an explicit biodiversity risk rule: the urban forest should contain no more than 5% of any one tree species, 10% of any genus, and 20% of any family. That’s a direct response to the real-world vulnerability cities face when too many streets rely on one species and a pest/disease arrives.

Melbourne also makes the strategy feel tangible at the street scale. One case study in the document describes Elm Street (North Melbourne), where a redesign using a new central median is projected to raise canopy cover from 18% to 65%, a clear example of how biophilia can be achieved through very specific public-realm geometry and planting space, not just “plant more trees.”

If you redesigned one corridor like Melbourne’s “Elm Street” example, what space would you take back to create canopy: parking lanes, a travel lane, or a new median?

Review

- A biophilic city is defined mainly by one large iconic park and decorative landscaping.

- Small and repeated experiences with nature can reduce stress and mental fatigue.

- Biophilic design works best when nature is continuous and connected across streets, neighborhoods, and buildings.

- A biophilic city focuses only on greenery, not on supporting wildlife or ecosystems.

- Biophilic goals succeed when cities include clear policies, long-term maintenance, and equity considerations.

- Singapore’s Park Connector Network makes nature part of daily commuting and movement.

- Portland’s Green Streets program consists of only a few showcase rain gardens.

- Melbourne’s Urban Forest Strategy limits overreliance on one tree species to reduce risk from pests and disease.