Humans have always chased one simple goal: staying out of the “too hot” and “too cold” zones. Long before compressors, chillers, and smart thermostats, people experimented with fire, stone, wind, water, and building form to make indoor life more comfortable. Some of those early ideas were surprisingly sophisticated, and many still matter today, especially in places where mechanical HVAC is rare or unreliable.

This journey looks at how people across history tried to control temperature using architecture (building form and materials), nature (sun, wind, shade, water), and simple technology. We move through different climates and cultures to see how comfort was created long before modern machines.

Activity 1 – Why Temperature Control Matters

Staying in a “comfortable band” of temperature isn’t just a luxury. It affects health, sleep, focus, and even how long people can safely work or study. In cold climates, a failure in heating can be life-threatening. In hot climates, extreme heat combined with high humidity can push the body close to its limits. Across history, temperature control has shaped how people cook, sleep, gather, and design their homes and streets.

You can think of this journey first as a story about survival, which slowly turns into a story about comfort and convenience. Early solutions are very local and clever, using what the climate and materials offered. Only much later do we lean heavily on high-energy mechanical systems.

Think about your typical day. Where do you feel temperature most strongly, outdoors, in transit, or inside certain buildings?

Activity 2 – Early Heating Systems with Fire and Floors

The earliest “system” for heating was simply fire in a space: a hearth in the center of a room, with smoke escaping through a hole or a basic chimney. Over time, different cultures found ways to move heat more intelligently, rather than letting most of it escape with the smoke.

In the Korean “ondol” tradition, a fire was lit in an external or semi-external hearth, and hot smoke traveled through channels under stone floors before exiting through a flue. The heavy floor acted as thermal mass—materials that can store heat and release it slowly—creating something very similar to modern radiant floor heating.

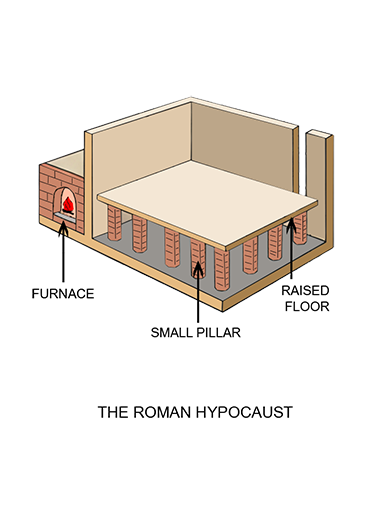

The Romans developed a related idea called the hypocaust: a raised floor supported on small pillars, with hot gases from a furnace flowing underneath and sometimes up through wall flues. Rooms, especially baths, were warmed from below and from the walls, not just from a single fire point. In both systems, the building itself became a heat battery, holding warmth even after the fire died.

In your climate, would you rather sit beside a hot air vent or on a warm floor? Why?

Activity 3 – Thick Walls, Courtyards, and Shade

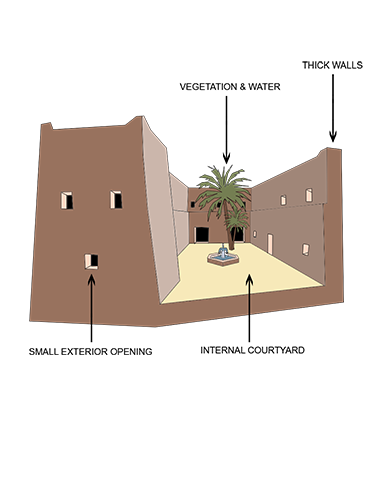

In many hot or dry regions, the main problem was not producing heat but blocking excess heat. People relied on building forms as a shield. Thick stone or adobe walls, small exterior openings, deep window recesses, and internal courtyards are common patterns in traditional architecture across the Mediterranean, the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Asia.

Here, thermal mass works in the opposite direction: during the day, heavy walls absorb heat and slow its movement into the interior; at night, they release that stored heat back out, smoothing daily temperature swings. Courtyards collect cooler night air, allow hot air to rise and escape, and often include vegetation or water to create small microclimates (local pockets of slightly different temperature and humidity). These tools, mass, shade, and controlled openings, show how architects used form and material as their primary “equipment” for temperature control.

If you had to design a house in a hot, sunny climate, what would you choose first: thicker walls, a shaded courtyard, or bigger roof overhangs? Why?

Activity 4 – Early Fans and Air Movement

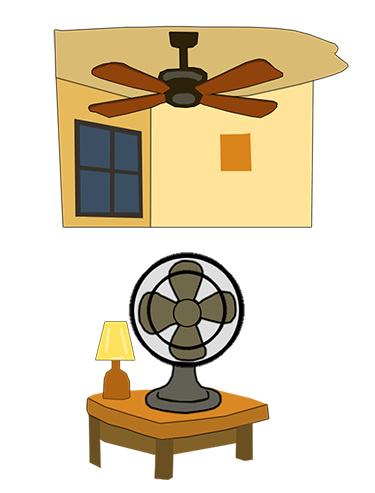

Air movement changes how we feel the temperature, even when the actual air temperature stays the same. A breeze increases evaporation from our skin and makes warmth more tolerable. Still air can make even moderate heat feel heavy and exhausting.

Long before electric fans, people found ways to move air using wind, water, and muscle. In some traditional Middle Eastern and North African towns, tall windcatchers (also called wind towers) were used to scoop prevailing winds and channel them down into interior spaces. Air often passed over pools or fountains, adding a bit of evaporative cooling—cooling caused by water evaporating and taking heat with it. In parts of Asia, large fans were once moved by hand or by simple mechanisms, and later by water wheels. Indoors, hanging cloth punkahs were pulled back and forth to move air across groups of people. All of these devices show that sometimes the smartest move is not to cool the air drastically, but to move it so bodies can cool themselves more easily.

Think of a very hot day you remember. Did a breeze, fan, or moving air make it feel significantly more tolerable, even if the temperature was still high?

Activity 5 – Improved Fireplaces, Stoves, and Chimneys

As buildings grew larger and urban life became denser, simple open fires were no longer enough. People needed heating that was more efficient, less smoky, and safer. This led to many experiments with improved fireplaces and stoves. Heavy masonry stoves in colder regions, such as tiled stoves in Central and Eastern Europe, often use long flue paths through brick or ceramic bodies. The hot gases warmed the stove’s mass, which then slowly released heat for many hours. Again, thermal mass turned a short, intense fire into long, steady comfort. In 17th-century France, designers like Louis Savot experimented with “circulating” fireplaces that pulled cooler room air in near the floor, warmed it behind or around the firebox, and then released it higher up. Later designs added dedicated outside air for combustion to prevent the fire from consuming too much indoor air. These were incremental but important steps: more heat delivered to the room, less smoke, and better control.

In a cold winter, would you personally prefer sitting near a radiant stove or relying on warm air blowing from vents throughout the room?

Activity 6 – Ice, Cold Storage, and Early Refrigeration

For most of history, true “cold” indoors depended on the climate. In cold regions, people harvested natural ice from lakes and rivers and stored it in well-insulated icehouses for use in warmer months. In hotter regions, this method was unreliable or impossible. In the 1840s, physician John Gorrie in Florida argued that cooling was essential for health in hot, humid environments. Because imported ice was expensive and limited, he began experimenting with artificial ice-making. His machine used a compressor (driven by steam or other power) to circulate a gas, cool it, and create ice. In 1851 he received a patent for his design, but he failed to secure the funding needed to scale it up and bring it into everyday use.

Even though Gorrie’s experiments did not become common at the time, they marked a shift from relying purely on natural cold toward mechanical refrigeration, intentionally creating low temperatures where the climate would not usually allow it. Imagine living in a hot climate before mechanical cooling. Would you focus more on improving building design (shade, night ventilation, courtyards) or on finding ways to store or create ice to retain food?

Activity 7 – Electricity, Fans, and Early Air Conditioning

The arrival of reliable electric power transformed temperature control. Electric motors made it possible to use rotating fans almost anywhere. Ceiling fans and oscillating fans appeared in homes, cafés, and public buildings, adding adjustable air movement at the flip of a switch.

At the start of the 20th century, engineers began to combine refrigeration and air movement into systems that look very familiar today. In 1902, Willis Carrier designed a system for a printing plant that controlled both humidity and temperature by passing air over cold coils. It was intended to stabilize paper and ink, but it became known as one of the first modern air-conditioning systems. In the years that followed, larger centrifugal chillers and smaller room coolers brought this idea into theaters, offices, and eventually homes.

By the mid-20th century, many buildings in some countries were being designed under the assumption that mechanical air conditioning would provide comfort. That assumption changed building forms, window sizes, and even where people chose to live. Which invention do you think changed indoor comfort the most: electric fans, air-conditioning machines?

Activity 8 – Connecting Historical Strategies to Modern HVAC

Across history, comfort depended first on climate-aware design, not machines. Thick walls, shaded courtyards, narrow streets, wind catchers, and night cooling all show the same idea: use sun, wind, and materials intelligently before adding technology. Many places still rely on these methods because full mechanical HVAC is too expensive or not always available. For designers today, the main lesson is to start with the building itself, orientation, shading, natural ventilation, and thermal mass, then let mechanical systems support what architecture already does well, instead of fixing what architecture ignores. This creates buildings that are more resilient, more efficient, and often more pleasant to occupy. It also sets up the next step: exploring modern HVAC systems and understanding how they can work together with these nature-based strategies rather than replace them.

List the: the passive (nature-based) strategies you can implement before the mechanical HVAC system. Appreciate indoor temperature comfort!

Review

- Temperature control affects health, sleep, focus, and safety, not just comfort.

- The Roman hypocaust and Korean ondol systems used the building itself to store and release heat.

- Thick walls in hot climates help buildings cool down by quickly letting heat pass indoors during the day.

- Moving air can make people feel cooler even if the air temperature does not change.

- Masonry stoves use thermal mass to release heat slowly over many hours.

- John Gorrie successfully mass-produced artificial ice for widespread use in the 1850s.

- Willis Carrier’s early air-conditioning system was originally designed to control humidity and temperature in a printing plant.

- Modern HVAC should support and work with climate-aware design strategies, not replace them.

- Everyone in the world has access to Heating, Ventilating, Cooling Mechanics.

- Only 25% of the world has access to heating and cooling.